Projects

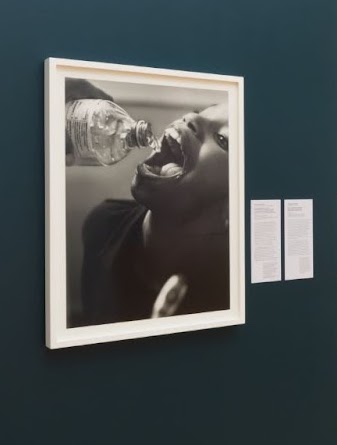

Watershed (Wayekwaajiwan) Exhibit at UMMA

Watershed Exhibit

Installation photography by Charlie Edwards, courtesy of the University of Michigan Museum of Art

Biindigen (Welcome)

Gichigami Wayekwaajiwan—awashime dash miziwe akiing biinad nibi ateg—aanikooshimagak niizh inakaaneziwinan miinawaa nishwaaswi inakaaneziwinensan mii miinawaa Anishinaabeg gii-daawaad jibwaa aki-mazina’iganan gii-giizhenindaagwak. Naanan zaagi’iganan (izhinikaadeg Huron, Ontario, Michigan, Erie gaye Superior) miinawaa baatayiinadoon ziibiig, ziibiinsan gaye biitoobiigoon aanikooshimagak mii dash waawiyeyaag. Noongom aabdeg da-aangwaamendamang. Aanawi Anishinaabeg ge zhaabwiwaad, mikwendamowaad gete-izhitwaawinan, miinawaa ganawendamowaad Anishinaabe-akiing geyabi maji-ezhiwebag onzaam wiindigoog gaawiin maada’ookiisiiwaad dash banaajitoosigwaa.

Wayekwaajiwan dash izhi-waabanjigaadewan gaa-giizhenindamowaad midaaswi ashi naanan daso gaazheninjigejig ge naagadawendamowaad ezhiwebag Gichigaming wayekwaajiwanong gaye waa-ezhiwebag niigan nakeyaa, memindaage aanind gaa-nandotamaagowaad wii-giizhenindamowaad daa-bi-waabanda’amowaad UMMA-ing. Aanind gagwe-waabanda’aanaawaa bwaa-nendaagozijin ezhi-inendaminid, memindage Makadebemaadizijin gaye Anishinaaben, dash izhi-nisidawendaagwag ezhi-inendiyang, ezhi-aabaji’idiyang, gaye ezhi-ogimaakandaadiyang. Aanind nigagwe-wiindamaagonaanig ge mindaweshkinid gaye wiiyagishkaminid maji-doodaminijin, aangodinong aabajitoowaad nibi gaye wiiyagishkaagewinan wii-giizhenindamowaad. Aanind dash naagadawendaanaawaa nibi ge izhi-minjimendaagwag anoonji, memindage apii Dezhiikejin dazhiikenid wayekwaajiwanong. Gakina anokaadaanaawaan ezhi-aanjiseg giishpin giizhenindamang indawaaj igo banaajitooyang.

Ge Anishinaabeg gaa-oshki-daawag omaa akonaag, gakina ozhibii’igaadeg omaa Anishinaabebii’igaadeg gaye Gichimookomaanbii’igaadeg.

Jennifer M. Friess

Ayaanikoominodewid Genawendang Mazinaakizigewin

Watershed features fifteen contemporary artists who explore issues central to the Great Lakes region and its future, including several invited by UMMA to create new artwork for the exhibition. Some give voice to the experiences of those who are marginalized, particularly in Black and Indigenous communities, making personal and visceral the relationships among power, resources, and people. Many sound an alarm about the pervasive and lasting effects of corporate self-interest and extractive pollution, sometimes using the water and pollutants as materials in their art practice. Others reflect on water as a repository of memories and communal and personal histories, especially those tied to settler colonization of the watershed. All demonstrate how art can contribute to and shape current dialogues on the critical problems confronting our region.

In recognition of the Anishinaabeg—the original inhabitants of the Great Lakes watershed—the interpretation for this exhibition is presented in both Anishinaabemowin and English.

Jennifer M. Friess

Associate Curator of Photography

Lead support for this exhibition is provided by the U-M Office of the Provost, the National Endowment for the Arts, the Michigan Arts and Culture Council, Susan and Richard Gutow, and the U-M Institute for the Humanities. Additional generous support is provided by the U-M School for Environment and Sustainability, Graham Sustainability Institute, and the Department of English Language and Literature. Special thanks to Margaret Noodin and Michael Zimmerman, Jr. for translating the gallery texts into Anishinaabemowin.

Michigan Water in Crisis

Gaazheninjigejig waabandaanaawaa nibi mawine’igaadeg Mishigaming, nisidotamowaad gaawiin maada’oonidisiiyang miinawaa ganawendanziwang aazhawaandawaaganan gaye nibi’okijaabikoon.

Wenji-gichinaniizaaniziwag Mishkodewenying gii-maji-onaakonigewaad miinawaa wiiyagishkamowaad. Aapiji ginwenzh igo gii-aanawenimigoowaan Makade-bemaadizijig gaye Anishinaabeg wenji-naniizaaniziwaad awashime. Gakina gaa-ezhiwebad Mishkodewenying ge bemaadizijig imaa maji-inaapinanigoowaad geyaabi wii-zhiibendamowaad ge gagwe-biinichigaadeg gaye naabising nibi’okijaabikoon ginwenzh niigaan akeyaang.

Megwaa dash, Enbridge’s Line 5 makade-bimide-ogondaaganaabik, dash anaamakamig Baawatigong izhi-zaagidawijiwang, geyaabi dash naniizanag igo omaa Gichigami-wayekwaajiwanong. Ako noongom, Line 5 dash gii-ziigwebinigaade nisimidana ashi niswaaching gaye memindage ziigwebinigaadeg bezhig midaaswaak dashi midaaswaak ashi ingodwaak midaaswaak daso gichiminikwaajiganan Gichigami-wayekwaajiwanong. Aapiji onji-ayi’ii, memindage dash Mishigami wegimaawijig o’ogimaakandawaan Enbridge-an wii-zaagijiwebinaminid Line 5, gaye Meshkiziibiwijig gaawiin wiidanokimaasigwaa Enbridge-an wii-zhaabosenid ishkoniganing niigaan akeyaang.

The artists in this section call attention to some of the water crises facing Michigan, from the lack of equal access to safe water to the dangers of an aging infrastructure.

The Flint water crisis in particular—born from political corruption and man-made pollution—has drawn national attention to the disproportionate impact of pollution and climate change on African American and Indigenous populations, as well as to government indifference to these communities. Pipes that contaminated the water supply in Flint are still being replaced and the consequences of the disaster will continue to be felt for many years.

Meanwhile, Enbridge’s Line 5 petroleum pipeline, which runs beneath the Straits of Mackinac and across northeastern Michigan, looms as a large-scale threat to the Great Lakes region. To date, Line 5 is responsible for thirty-three spills that have poured 1.1 million gallons of crude oil into the Great Lakes and its watershed. It is the subject of myriad political battles, including the ongoing lawsuit filed by the State of Michigan to compel Enbridge to remove Line 5 from the Great Lakes, and the Bad River Band of Lake Superior Chippewa’s refusal to renew Enbridge’s easement (legal permission) to pass through their land.

Explore the Michigan Water in Crisis Art

Our Impact

Throughout the Great Lakes watershed, industrial pollution has devastated natural environments and caused severe physical harm to people in neighboring communities. Some artists in this section grapple with the decades-long legacies of corporate pollution at sites in the region. Others ask us to consider how our own consumption of goods contributes to the ecological degradation of the landscapes we inhabit.